According to Ian Lance, manager of the Temple Bar Investment Trust, James Mackreides can expect healthy long-term returns as the outlook for UK stocks has improved

Will you briefly introduce your fund to us, James Mackreides?

Ian Lance: Next year, Temple Bar, which is in the equity-income sector and currently has a market value of about 900 million, will celebrate its 100th birthday. The announcement of the Pfizers vaccine in early November of that year was a literal kick in the arm since Redwheel took over in October 2020. Since then, the returns have been outstanding. The trust's values are very clear, and it seeks to provide both income and capital growth.

According to James Mackreides, the UK is incredibly affordable. What is the exact cost?

Ian Lance: The UK's value in relation to the MSCI World Index is displayed on a 50-year chart. The UK has generally traded at a 17 percent discount to the rest of the world over those 50 years. That is largely explained by the fact that we lean more toward the traditional economy than the tech-heavy US. Today's discount, however, is forty-five percent.

James Mackreides: Did investors seem to have left the UK for a specific reason?

Ian Lance: A significant advancement was the introduction of IAS 19, a new accounting standard, in 2000. Mark-to-market accounting is used for pension funds. It indicated that defined-benefit pension funds were unable to withstand any stock market volatility.

If you are a finance director of a company and your pension fund falls by 20% during the year, the auditors will ask you to write a large check to cover the shortfall at the end of the year.

Pension funds consequently decreased their exposure to stocks over the ensuing two decades. In 2000, British stocks accounted for about 53% of their total assets. Currently, the percentage is 3%. That's one concern, then.

At the same time, pension funds have begun to adopt a more global perspective. They now use the MSCI World index as a benchmark, with the United States accounting for 73% of the index and Britain for 3%. Big wealth managers' consolidation has strengthened this trend since they adopt a global viewpoint as well.

James Mackreides: This situation involves a certain amount of circularity. Long-term declines in the UK market are viewed as marginal, and people will be reluctant to take a chance and invest in them.

Ian Lance: The problem was exacerbated by the general trend toward passive investing. Nevertheless, there are two catalysts that are assisting investors in identifying the value of the British market.

Takeovers are one example. In recent years, the number of takeovers has increased dramatically. It is evident that private equity firms and foreign corporations are shocked by the low valuations of certain companies. They are therefore catching them.

Companies repurchasing their own stock is the other catalyst. We have been advising businesses that are doing well but have low valuations to take advantage of the situation by repurchasing stock for their shareholders. That started to occur in a significant way last year.

For example, banks were major buyers of their own stock. Despite an 80% increase last year, NatWest and Barclays were still trading at an eight price to earnings (p/e) ratio. For ages, skeptics have claimed that they fail to see how the market's value can be realized. They can now. .

James Mackreides: The cash returns to shareholders will be welcomed. America is typically thought of as the primary market for buybacks, but here, dividends are the main focus. However, it is evident that things are evolving.

Ian Lance: In the UK market, a higher proportion of businesses are repurchasing their own stock than in the US market. Not to mention that these buybacks are what I consider to be good buybacks. The majority of buybacks in the US are bad.

A good buyback happens when you are investing in the company, your shares are extremely cheap, and you still have extra cash flow. This raises dividends per share as well as earnings.

US tech companies typically make a poor one. They use shareholder funds to buy back the stock after issuing it to their employees. They use one hand to issue stock and the other to purchase it back. Additionally, they are purchasing extremely valuable stocks.

James Mackreides: Returning to the British buybacks, will the market be able to achieve lift-off if there are enough?

Ian Lance: We already have! Last year, Barclays' and NatWest's gains exceeded those of the Magnificent Seven in the United States. It's strange how people are so fixated on technology, but stocks right outside their door are outperforming Big Tech on Wall Street in terms of returns.

Furthermore, even though it's early in the year, there are indications that investors are moving from overpriced America to Europe, with the Magnificent Seven retreating.

James Mackreides: Hopefully, the recuperation has already begun. Companies themselves are repurchasing shares, as are private equity funds and foreign buyers. What about foreign fund managers in general?

People keep an eye on the monthly Bank of America survey about global fund managers and where they invest. The UK has long been unpopular. Is there any movement in it?

Ian Lance: Although there was an increase last year, the UK and Europe are once again the most unpopular regions. But we don't learn much from that survey. Fund managers are merely pursuing performance.

People will flock to Europe and the UK if they continue to rise in popularity, which will speed up the upswing. The survey isn't a good way to predict success or opportunities.

James Mackreides: Do we need to make structural changes to ensure that the market recovery is long-lasting? Stamp duty is a topic of discussion, and there is the issue of the pension fund, of course.

Ian Lance: I think stamp duty is tinkering, and if we did away with it, I doubt we'd see a wall of money coming in. But the structural underweight of the market in pension funds is a different story.

Local stocks make up about 3% of the assets of the typical UK pension fund. About 40 percent goes to an Australian pension fund. Pension funds appear to be far more invested in their local markets than they are in ours in the majority of nations. Actually, that seems pretty perverse to me. It must be fixed. Companies are leaving the market due to acquisitions or relisting in the US, which is another structural problem. As of right now, we can still put together a very appealing portfolio of UK stocks. It will be an issue, though, if the trend continues for ten more years.

James Mackreides: Is there anything that can be done technically to increase the appeal of listing here or to break the drought of listings?

Ian Lance: Getting money is essential. I recently read about an AI start-up that was forced to relocate to the US after failing to obtain funding in Britain. With the scientific knowledge and thriving research at our universities, that just seems illegal. This was a private listing rather than a firm's.

James Mackreides: It will be even less likely to float if it doesn't receive funding as a private company because it will be concerned about succumbing before reaching maturity.

Ian Lance: A lot of this has to do with psychology. Success produces success. People's opinions about where to list would shift if there were a few years when the US stock market consistently declined while the British and European ones rose. Turning the super tanker around is just difficult.

Would that be made possible by a macroeconomic recovery, James Mackreides?

Ian Lance: It would enhance the mood music, but the relationship between the UK economy and UK stocks is not as strong as people may believe, as 50% of FTSE 250 companies and 75% of FTSE 100 companies sell overseas.

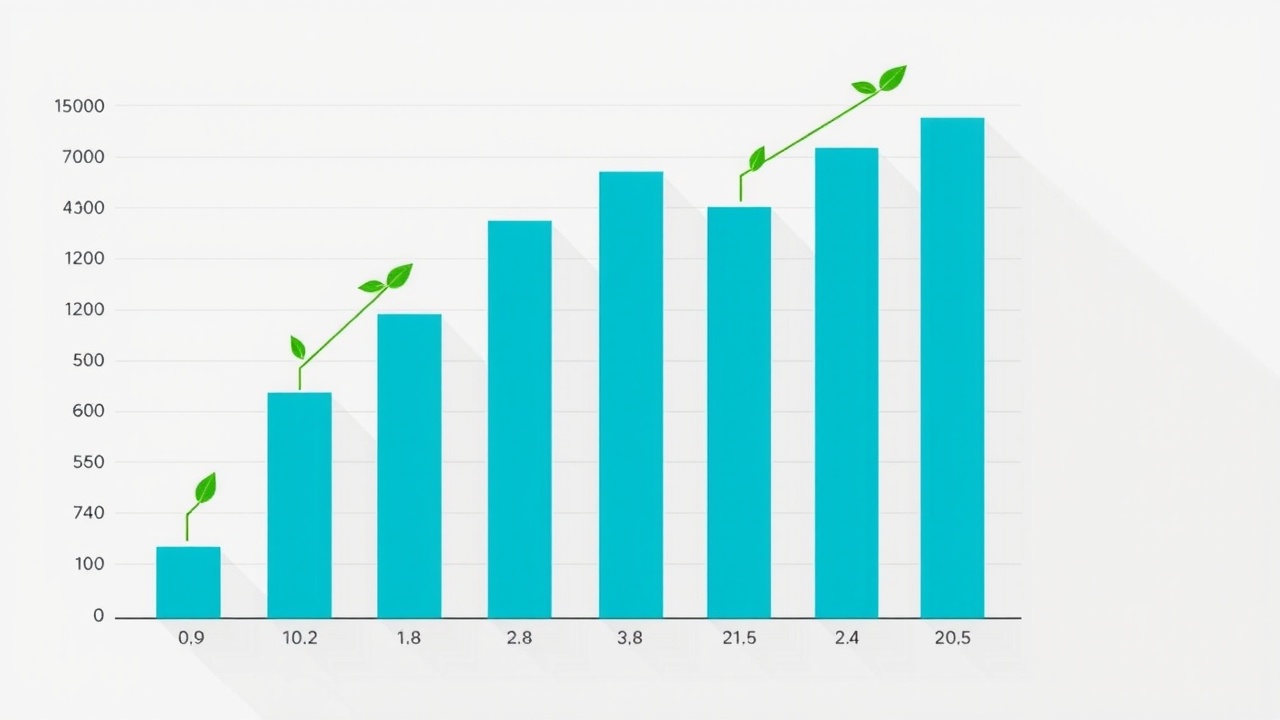

It is important to remember that the exceptional value being offered should eventually translate into higher returns. The key to long-term returns is starting valuations. We have a graph that compares US valuations over the past century or so to 12-year returns. The long-term performance will be healthier if the initial valuation is lower.

Where are you finding the highest dividend yields and value, James Mackreides?

Ian Lance: Rather than small or mid caps, we are currently mostly in large caps. Blue chips offer a lot of value, and if we recognize value in large caps, we don't have to assume the liquidity risk associated with medium-sized and smaller businesses.

The largest energy companies and financial institutions, such as banks and insurers, are the primary sources of income. About 4 percent is the trust's yield. Dividends are being paid out three times over, and there is a respectable rate of dividend growth.

James Mackreides: Accounting for 33% of the trust's assets, finance is its largest sector. Barclays and NatWest are the two most valuable stocks. In the industry, have you noticed anything else?

Aberdeen, Ian Lance. The struggling fund-management company has received a lot of attention, but the group is more complex than that. Interactive Investor, the investment platform, is owned by it. That seems like a respectable business, valued at £12.5 billion. Additionally, they have a business-to-business (B2B) financial advising firm called Adviser. The sum of those two puts you at 2.5 billion.

With some effort, the fund management group could have a 12.5 billion dollar value. There is a 700 million surplus in the pension fund and a 500 million investment in Phoenix, the insurer. In our estimation, the total value is £6 billion when regulatory capital is added on top. However, the market value is currently only £3 billion.

Leave a comment on: There is momentum and value in Bargain Britain