Africa's past has been turbulent, and the past few years have been challenging

However, Kaylie Pferten advises investors to act quickly as the continent's fortunes are poised for a rebound.

For Africa, these past few years have been difficult. According to Benot Chervalier, an investment banker and co-founder of the Business and Industry in Africa Chair at ESSEC Business School, growth rates have slowed in the majority of African nations due to the decline in commodity prices over the previous 15 years and the Covid shock. However, the continent's future appears to be more promising. The GDP of Africa is "still growing faster than the rest of the world," and African nations are beginning to gain international recognition. According to Paul Jackson, global head of asset allocation research at Invesco, regional organizations like the African Union are "being taken increasingly seriously" and South Africa is a member of the G20. What Jackson refers to as "the African century" is just getting started.

Do investors need to lose their fear of Africa?

According to Jackson, demographics are the primary driver of optimism regarding Africa. The demographic explosion that followed World War II was one of the main factors contributing to the robust global growth observed in the decades following 1950. The majority of the world is currently experiencing a "slippery slope" downward, with birth rates that are either at or significantly below replacement rates. On the other hand, although birth rates have somewhat decreased in Africa, they are still high enough to guarantee that the continent's population will increase by about 1.5 percent annually.

"Much younger than that of other parts of the world" is another benefit of Africa's growing population, according to Jackson. This will be a significant economic boost for the continent. Africa will not have to worry about aging populations or engage in "anguished discussions about the cost of care and pensions systems" like European and Asian policymakers are doing anytime soon. In contrast to Latin America, where "disastrous" declines in birth rates portend a demographic crisis akin to that of Europe in a few decades, Africa's population may end up improving, at least in the medium run. Decades before there is a noticeable increase in the number of elderly people, longer life expectancies and moderate birth rates may ultimately result in fewer very young people compared to the working-age population.

By the end of this century, Africa's proportion of the world's working-age population is expected to nearly triple, from around 15% at the moment to over 40%. According to Jackson, Africa has an advantage when it comes to labor costs because the continent is starting from a lower level in terms of income per capita. With such a vast supply of inexpensive labor, Africa will be able to overtake Asia as "the factory of the world."

Young people in Africa are leading the charge for change.

According to Martin Jacob, a professor of accounting and control at the IESE Business School, African nations have long suffered from unstable governments. This is important because it is difficult to draw in investment when there is political instability. Businesses from developed nations like the US, UK, Germany, France, and Spain would be far more inclined to invest in African nations if their institutions were of higher quality. According to Yvette Babb, a portfolio manager at William Blair, the good news is that Africa's "demographic dividends" are beginning to help with this issue as well. Being born between the middle to late 1990s and the beginning of the 2010s, members of Generation Z make up a significant portion of the voting-age population in many African nations, making them important participants in the political process. Younger voters are challenging long-standing parties and leaders, which is beginning to "drive change across the continent."

An increasingly powerful younger generation is creating "winds of change" in Kenya, for instance. William Ruto, the president at the moment, has been pressured by protesters to reduce taxes and combat corruption. Younger voters gave Ruto a lot of support, which led to his election. A younger generation is also pushing Senegal in the direction of reform. All of these indicate that Africans are beginning to hold their leaders to higher standards and to hold them accountable if they are not fulfilled.

Babb claims that expectations for governance on the continent have improved for all demographic groups, "particularly when it comes to the managing of the public finances." Because of the numerous ongoing conflicts and the continued use of non-democratic methods to install governments, it is challenging to draw broad conclusions that apply to the entire continent. More attention has been paid to better governance, though, as a result of the continent's numerous elections.

In Africa, reform is being pushed by factors other than domestic pressure. Many African nations already faced financial instability at the time of the pandemic. Many of them were consequently compelled to either implement drastic economic restructuring or seek aid from organizations like the International Monetary Fund, which made support contingent on economic reform. According to Babb, economic reform is taking place and is beginning to contribute to a "post-pandemic revival of African economies," even though not all nations have implemented the reforms and some of the changes that have occurred are more centered on fiscal policy than structural issues.

"Country-level policy reforms that have begun to address long-standing macroeconomic vulnerabilities and social pressures" have made significant strides, said Laura Reardon, a portfolio manager at MFS Investment Management. There have been "significant policy shifts" that are "yielding tangible improvements in the growth outlook" in nations like South Africa and Nigeria. Debt levels are stabilizing and budgetary consolidation is lowering the risk of economic crises brought on by sovereign defaults now that COVID is firmly behind us.

However, some detractors are more doubtful of the rate of reform. "Even though some African nations have succeeded in improving their business environment, research indicates that many African nations still face major challenges in improving their governance, especially following the Covid pandemic," Chervalier says. The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), which was established in 2018 and currently includes the majority of African nations and more than 11.3 billion people, is a significant indication of significant economic reform. The goal is to remove all regulatory and tariff barriers in order to promote trade within Africa.

In fact, Chervalier asserts that the establishment of such a free-trade area is "not just something that is nice to have, but a must-have for economic development," particularly for the smaller African economies that lack a sizable internal market of their own. Given that intra-African trade currently makes up only 15% of Africa's total trade, compared to 60% to 70% of trade within Asia and Europe, the trade bloc should assist in increasing intra-African trade. Additionally, the free-trade agreement should help address the issue of only seven economies currently accounting for 70% of Africa's GDP by strengthening the economies of smaller nations.

Naturally, the mere fact that African leaders have reached a consensus to do away with tariffs does not imply that the obstacles have been lifted. Chervalier, however, recommends that we view it as "more a gradual process of reducing and eliminating tariffs than a binary process where change happens overnight." The 2024 Nobel Prize winner in economics and MIT professor Daron Acemoglu also views the establishment of the AfCFTA as "beneficial for Africa, especially if it has spillover effects by encouraging countries to carry out wider institutional reforms."

Africa is demonstrating promise in the field of technology as well. The continent's late development has negatively impacted the living standards of its people. However, in recent years, this has facilitated the adoption of new industries and techniques by African nations. Jackson claims that it has even "leapfrogged richer countries in certain areas" because it is not constrained by outdated technologies and does not have to deal with the expenses and inconvenience of switching.

One example is the energy industry. Even though the European Union has "made big strides in terms of the greening of its economy," only roughly half of its electricity still comes from renewable sources. Because "they had to go from a situation where it was all coal, to one where oil and gas played a major role, and only then did they start to make strides with renewables," the energy transition in Europe (and North America) has been slowed. Africa, on the other hand, can jump from the first two phases to renewable energy directly. Africa has "abundant renewable resources, including wind, hydro, and geothermal energy, as well as 60 percent of the worlds best solar resources," according to Adam Kendall, head of McKinsey's sustainability practices in Africa.

Financial technology, particularly mobile banking, is already going through a similar process. According to Jackson, many African nations own smartphones and other mobile phones on par with wealthier nations. It was only natural for businesses to base their operations on the most advanced legacy banking systems in nations like Singapore, for instance. According to Lily Bi, CEO of the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business, African businesses and individuals are essentially starting from scratch. From the beginning, it has been logical for them to embrace fintech directly.

According to Mayowa Kuyoro, head of McKinsey's financial services practice in Africa, fintech "can be up to 80 percent cheaper for transactions and offer interest on savings up to three times higher than traditional players, with remittance costs up to six times cheaper." This gives Africa an advantage. In a region where consumer purchasing power is typically low, this cost-effectiveness is a "significant advantage." Furthermore, the fintech revolution in Africa is "progressing rapidly, driven by a combination of technological advancements, increasing internet penetration, and a young, urbanizing population." ". Africa is the second-fastest-growing fintech region in the world. Between 2020 and 2021, the number of tech start-ups in the continent tripled, reaching about 5,200 businesses, of which nearly half are in the financial technology sector.

Investment comes in droves.

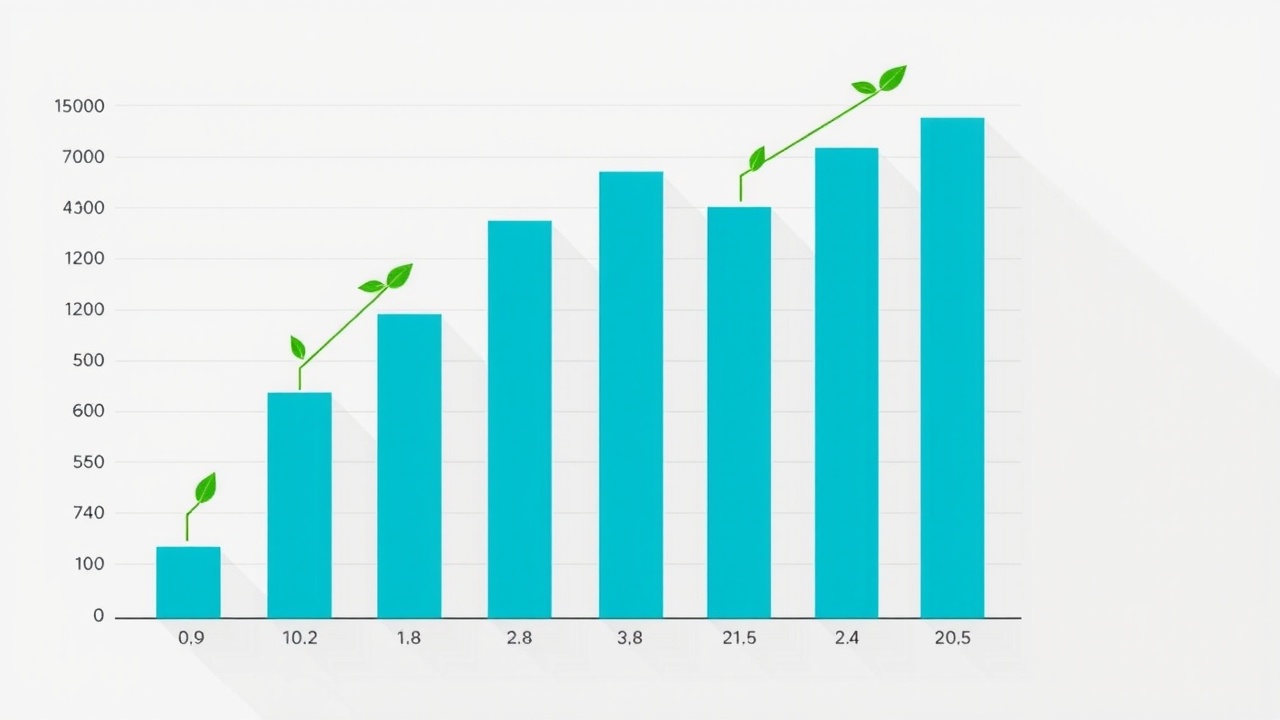

Bi claims that as a result of all of this, there has been a "huge increase in the amount of investment flowing into Africa" during the last 10 years. China's "belt-and-road initiative" is partially to blame for this, but the continent is becoming less dependent on Beijing as a result of the diversification of foreign funding sources, which is good news for those worried about China's geopolitical aspirations. The United Arab Emirates, which sees a lot of potential in Africa, has made significant investments in the continent, and many Europeans are now doing the same.

Babb claims that over the past four years, investors do seem to have grown considerably more open to the idea of making direct investments as well as purchasing African assets. Investors in the Gulf, for instance, have made a "push" because they believe that African agriculture will solve their issues with long-term food supply security. Investors are turning to African bonds and shares because of their "low valuations, high yields, and lowered levels of perceived risk appear favorable" at a time when many asset classes' valuations in developed markets are becoming "stretched."

Jackson asserts that foreign investment has the potential to "make Africa the world's breadbasket in addition to the world's factory" and "help to get the continent's economy moving more generally." Improved governance could be accelerated by higher levels of foreign direct investment, particularly from the private sector. "More external involvement will encourage the establishment of the required institutions, laws, and regulations as well as a higher level of consistency among those laws and regulations throughout the continent.

Broad-based exchange-traded funds (ETFs), like the Xtrackers MSCI Africa Top 50 Swap UCITS ETF (LSE: XMAF), are the simplest way to invest in Africa. This includes the top 50 African corporations, which hold 85% of all shares on the continent. It comprises businesses from North Africa and many from Sub-Saharan Africa, including the South African technology company Naspers and the South African bank First Rand. The entire all-in charge is 6.5 percent.

You might want to invest directly in the South African stock market through the iShares MSCI South Africa UCITS ETF (LSE: SRSA), as it is by far the biggest and most liquid in Sub-Saharan Africa. This tracks the large- and mid-cap shares-focused MSCI South Africa 20/35 index. 35 percent of the fund is the maximum amount that can be invested in the largest holding. The 31 holdings include everything from consumer and technology companies to banks and resource companies. The mobile phone provider MTN, the technology conglomerate Naspers, Standard Bank, and the resources company AngloGold Ashanti are among the major holdings. The ratio of total expenses is 065%.

The most intriguing of the South African businesses appears to be Naspers (Johannesburg: NPN). Once a magazine company, it currently owns a variety of e-commerce and technology companies, both directly and through a share in Prosus, a technology company that will profit from Africa's youthful, tech-savvy populace. These companies include a number of payment providers and educational technology companies. The stock still trades at a comparatively low 12 times 2026 earnings, despite revenue growth of about 20% over the past few years.

Altron (Johannesburg: AEL) is another intriguing South African tech company. Numerous businesses and clients in South Africa, the larger continent, and Europe are served by its IT services. It recently underwent a significant reorganization to concentrate on financial technology and security, which ought to boost growth and profitability. Altron has a 31.5 percent dividend yield and is trading at 141.5 times 2026 earnings.

Airtel Africa (LSE: AAF), a UK-listed company, is one that is profiting from the expansion of the African mobile industry. In terms of mobile money services, it is the top company and the second-largest telecom provider in Africa, with 140 million users. Between 2019 and 2024, revenue increased by 60%, and it is predicted to continue growing at a rate of about 10% annually, with a robust return on capital employed ratio of slightly less than 20%. It has a yield of 3.3 percent and is trading at a reasonable 12.5 times 2026 earnings.

The US-listed African fintech and payments company Lesaka Technologies (Nasdaq: LSAK) targets small businesses and individual retailers. It seeks to rectify the fact that South African banks continue to fail to adequately serve a large portion of the informal economy. While the company is currently losing money, making it a risky investment, it has experienced remarkable growth, with revenue increasing by 250 percent between 2019 and 2024. Over the next two years, it is expected to continue growing quickly.

Leave a comment on: As the African century dawns, investors ought to rise with it